Equestrian Statues Ranked

Some of my picks will shock you

10 King Jagiello Monument (Central Park, New York City)

This badass statue of Władysław II Jagiełło (King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania) with double swords crossed over his head is one of my favorites in Central Park. It commemorates the 1410 Battle of Grunwald and was sculpted from bronze by Stanisław K. Ostrowski for the 1939 New York World’s Fair as a replica of a monument in Warsaw which was melted down and turned into bullets after the Nazis invaded that city. This is something that happens quite a bit with equestrian statues: there was one of King George III downtown at Bowling Green that was turned into ammunition for the Revolutionary War on July 9, 1776 after the first public reading in New York City of the Declaration of Independence.

In any event, the exiled Polish government donated this statue to the city shortly after VE Day in 1945. This short film shows its origin location in Flushing Meadows-Corona Park in Queens on a different plinth.

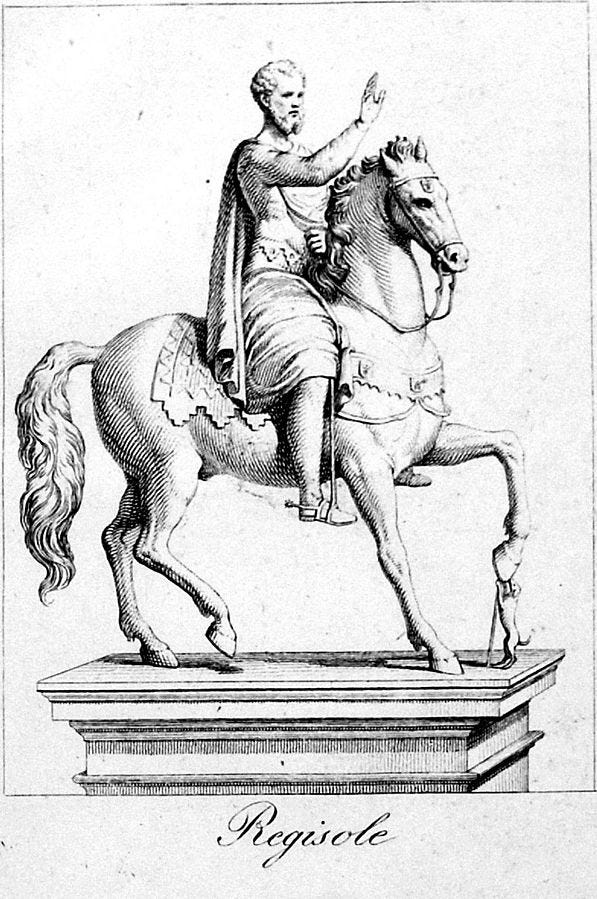

9 Regisole (Destroyed, formerly Ravenna and Pavia)

I’m ranking this relatively low only because it technically doesn’t exist any more. A reproduction commissioned by Mussolini in 1937 now stands in front of the Cathedral of Pavia but the original was destroyed for being a symbol of monarchy by the Jacobins in 1796. Nevertheless, Regisole (meaning Sun King) is of tremendous historical significance, inspiring all of the great equestrian statues of the Renaissance, and it was one of the most important artifacts to survive from classical antiquity.

The statue was originally in Ravenna, capital of the Roman Empire in the fifth century, and may have represented either Septimius Severus or Theodoric the Great. It was brought to Pavia possibly as early as the eighth century; the Arab traveler Ibrāhīm al-Turtuši saw it there in the tenth, and after a brief detour in Milan it was restored and placed in front the Pavia Cathedral in 1335. Both Petrarch and Leonardo da Vinci admired it, and Edward Gibbon praised it (especially the horse) about three decades before its destruction.

8 King Louis XIV (Versailles)

Stephen Colbert said you have to learn to love bombing and this equestrian statue definitely bombed on its debut. Louis XIV invited Bernini to Paris in 1665 to work on a new façade for the Louvre, although a different Colbert (French finance minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert) rejected the Roman artist’s plans for being too impractical. Bernini did however make a highly praised bust of the Sun King (not Regisole but rather the Roi Soleil Louis) and agreed to make an equestrian monument of the monarch upon his return to Rome.

The project was greatly delayed and ultimately finished by Bernini’s workshop in 1684, four years after the artist’s death. The next year it was shipped to Paris and then Versailles where Louis panned it, deeming the facial features a personal insult. The Sun King originally wanted the monument destroyed, but it was instead moved around various locations in the gardens of Versailles and eventually François Girardon recut the head to depict the Roman hero Marcus Curtius.

I think Louis XIV was overreacting. Bernini had modeled the work on his own Vision of the Emperor Constantine (see below), which in turn was influenced by Pietro Tacca’s 1642 sculpture of Philip IV of Spain, the first monument to display a rider on a rearing horse since antiquity. Nevertheless, when you’re the kind of guy who says things like L’État, c’est moi you’re probably not going to stand for an equestrian statue that’s not exactly what you want.

7 El Cid Campeador (Audubon Terrace, New York City)

This is an underrated equestrian statue by an underrated American artist. Anna Vaughn Huntington (née Hyatt) was the wife of Archer Milton Huntington, founder of the Hispanic Society of America. She created all the sculptures on Audubon Terrace, the courtyard in front of the museum, including this masterpiece of El Cid. She also made many other equestrian statues, including one of Joan of Arc on Riverside Drive and 93rd Street, NYC’s first monument dedicated to a historical woman, as well as one of José Martí in Central Park with a copy in Havana, several of Don Quixote, Sybil Ludington, and a young Abraham Lincoln reading a book on horseback. Talk about range!

Unrelated to equestrian statues, it is a historical quirk worth mentioning that Anna Hyatt Huntington was the aunt of the great print curator and scholar A. Hyatt Mayor who was the grandfather of Yeardley Smith, voice of Lisa Simpson.

6 Charles I (Charing Cross, London)

This is the oldest bronze statue in London and marks the official center of the capital from which all distances in the city are measured. In the Middle Ages an actual cross—from which Charing Cross took its name—stood on the spot, but this was destroyed in 1647 by Oliver Cromwell’s forces. The equestrian statue had been commissioned in 1630, the year after Charles dissolved Parliament, by Lord High Treasurer Richard Weston, to be situated in his country house’s garden in Roehampton, Surrey. The artist was the French sculptor Hubert Le Sueur.

After the end of the English Civil War, when Charles was beheaded, the statue was supposed to be melted down, but an entrepreneurial metalsmith appropriately named John Rivet hid it and sold, to both the Royalists and Parliamentarians, brass cutlery which he claimed had been made from it. Following the Restoration, the monument was seized and King Charles II placed the statue of his father in its current central location.

5 Vision of Constantine (Vatican City)

This is another underrated equestrian statue which is quite difficult to see unless you have special connections at the Vatican (which I don’t). Originally intended to be inside St. Peter’s Basilica itself, the sculpture ended up in front of the Scala Regia, the staircase serving as the official entrance to the Apostolic Palace, and as such it is only barely visible through a gate if you stand at the northern end of the narthex entrance portico of the Basilica.

Bernini received the initial commission in 1654 from Pope Innocent X. The subject is Constantine the Great seeing a miraculous cross in the sky before his victory against the pagan Roman Emperor Maxentius at the Battle of Milvian Bridge. As with many of Bernini’s projects there were delays, and work did not start until 1662. The location then shifted to the Scala Regia, also by Bernini, which necessitated further changes, and the statue was finally unveiled to very mixed reviews in 1669.

As a little bonus I’m throwing in an honorable mention to the Equestrian State of Charlemagne, dated 1725, by Agostino Cornacchini, which stands at the southern end of the narthex directly opposite the Vision of Constantine.

4 Bamberg Horseman (Bamberg, Germany)

I have not personally seen this statue and cannot vouch for it, but I’ve heard that it’s good. Carved from stone in the 13th century by an unknown artist, depicting an unknown king or biblical figure—theories range from Stephen I of Hungary to Frederick Barbarossa to one of the Three Wise Men—the Bamberger Reiter (to use its German name) stands near the north pillar of the choir in the cathedral of Bamberg. It is the first equestrian statue since antiquity and one of the first to depict a horse shoe.

The statue contains, on the support under the front hoofs, an example of a so-called Green Man, also known as a foliate head, that is to say a face made out foliage as a decorative motif. It also influenced, via a poem by the symbolist Stefan George, the failed 1944 attempt of Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg to assassinate Hitler.

3 Bartolomeo Colleoni (Venice)

We have some heavy hitters for the top three! Verrocchio (the teacher of Leonardo da Vinci) designed this monument although he did not live to see it completed. The subject is Bartolomeo Colleoni, a mercenary leader, who at his death in 1475 left a large sum to the Republic of Venice on the condition of equestrian statue of himself being erected in the Piazza San Marco. Statues, however, are not permitted there and so it was instead placed in front of the Scuola Grande di San Marco which is very much not the same thing.

A competition was held between Verrocchio, Alessandro Leopardi, and Bartolomeo Vellano and in 1483 Verrocchio won and started work. Unfortunately he died five years later and Leopardi had to finish it, unveiling it finally in 1496. The statue is an absolute masterpiece, depicting the horse in mid-stride with one hoof completely elevated and unsupported, creating a technical challenge for balancing the monument’s weight on the other three. Interestingly, Verrocchio probably never saw Colleoni so the work just depicts his impression of what a badass condottiero soldier of fortune should look like.

2 Gattamelata (Padua)

Donatello’s 1453 monument to the mercenary Erasmo da Narni, nicknamed Gattamelata (“honeyed cat”) is the first equestrian statue of the Renaissance and number two in my ranking. Gattamelata was born in Umbria and fought for numerous rulers in the Italian peninsula, including the Republic of Venice in their war against the Visconti of Milan. After his death in 1443 his heirs commissioned Donatello to erect this statue in Padua, the cost being split with the Venetian state although this remains somewhat mysterious since Gattamelata actually did not do a great job and Verona was lost under his command. In any event, the statue was more or less finished by 1450 and erected on a stone pedestal in main piazza three years later.

Donatello’s naturalistic masterpiece was indebted to the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius as well as Regisole and the Triumphal Quadriga on the loggia of San Marco in Venice. Unlike the dynamic motion of Bartolomeo Colleoni, Gattamelata is calm and still, one hoof of the horse resting on a cannonball. The monument is currently (as of October 2025) undergoing renovation so be ready for a spruced up Gattamelata in a few years.

1 Marcus Aurelius (Rome)

My top pick for equestrian statues is that of Marcus Aurelius in Rome. The original sculpture is now inside the Capitoline Museum but the image above shows a replica where Michelangelo placed it when he designed the Piazza del Campidoglio. It dates to about 174 CE although the original location is disputed; some say the Forum, others the current Piazza Colonna where the emperor’s column is located.

In any event, the statue was spared from being melted down after the fall of Rome because people in the Middle Ages misidentified it as depicting Constantine the Great, the first Christian emperor. There apparently was an equestrian statue of Constantine near the Arch of Septimius Severus which may have lead to the confusion. In any event, it remained on display near the Lateran Palace until 1538 when Pope Paul III had it moved to the Campidoglio.

With his calm poise and hand outstretched in the gesture of adlocutio, Marcus Aurelius basks confidently in knowing that his is the greatest equestrian statue of all time.

I would put King Jagiello a bit higher on this list. I mean, just look at him. He is ready.

You're probably de-sensitzed to his glory somewhat having lived there.