“All men by nature desire to know” said Aristotle in Book I of the Metaphysics. Add this now to the list of things the maestro di coloro che sanno got wrong, right up there with eels generating spontaneously from mud and women having fewer teeth than men. Even before the advent of large language model AI chatbots there were numerous news stories about declining interest in the liberal arts and about employers preferring so-called STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) graduates. Now, post-AI, we are inundated with stories about students who are functionally illiterate, have zero attention span, can’t comprehend Charles Dickens, and outsource all their homework to ChatGPT.

Certainly there is a crisis in American universities, much of it self-inflicted, but the crisis in the liberal arts, specifically related to the purpose of education, is a bit different and a bit confusing because of historical changes in terminology which I will examine in this post. The liberal arts, in today’s nomenclature, consist of the humanities, the social sciences, the natural sciences, and the fine arts. However, in the original meaning of the term there were seven liberal arts divided into two groups: the trivium (grammar, logic, and rhetoric) and the quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy). Depending on how you categorize things, roughly half of the original liberal arts are in fact STEM disciplines.

People who talk about the impracticality of the liberal arts, often expressed by the tacky American habit of asking what people are “doing” with their college majors, usually in fact mean the humanities. (Spoiler alert: the liberal arts are not job training and you’re not supposed to “do” anything except learn them.) There is in fact an even bigger crisis in the humanities than in the liberal arts and so I will be treating that topic in a separate post later.

The idea of the liberal arts that I am going to sketch out here may seem elitist and aristocratic because it very much was originally. At some point in the recent past people decided it would be beneficial if everyone were exposed to the same education that for centuries was exclusively for the upper classes. It turns out, however, that this is the last thing that most people want; most people would rather be credential-grubbing careerists than be educated. And although I love to roast Gen Z, they are in fact the least culpable for this messy conflation of education and job training. The bulk of the blame goes to (in order of most to least guilty) employers, university administrators, and faculty. I will touch on this point at the end, but this too will be expanded on a separate post because the topic is simply too vast.

Let us start the analysis of the changing meanings of the liberal arts and education by way of analogy, specially with the word classic and its variants (classics, classical, classically, etc.). Classic has a general meaning of being “of the first or highest quality, class, or rank.” It also has a more specific meaning of being “related to Greek and Roman antiquity.” Thus one can say “Shakespeare is a classic English author” and also “Shakespeare is not a classical author but Homer and Vergil are” and both are correct statements. Classical music can refer to what is sometimes called Western art music, encompassing everything from medieval Gregorian chant to Arnold Schoenberg’s atonality. Within classical music, however, there is also a Classical period, between roughly 1750 and 1820; in this sense, Mozart is classical but Bach and Brahms aren’t. In the visual arts, this same period is called Neoclassical, which means New Classicism and thus implies a rebirth of the classics—a rebirth that is completely different from the rebirths of the classics of the Carolingian Renaissance, the Ottonian Renaissance, the 12th century Renaissance, and (as I like to call it) the Renaissance Renaissance of the Italian Quattrocento.

In short, the term is a complete mess and if we were coming up with new labels from scratch today we would probably pick different ones.

A similar thing has happened with the terms education, liberal arts, and humanities. People often say they want education but they mean job training and occasionally vice versa. Consider the following institutions: the Ivy League or Ivy Plus, small selective liberal arts colleges, large state land-grant universities, professional colleges and graduate schools (law, business, medicine, etc.), seminaries, community colleges, and for-profit vocational colleges. In some generic sense they are all engaged in education, but the actual activities they do are so wildly disparate it stretches the term to the point of confusion. Some do basic research, advancing human knowledge with no predetermined practical aim; some instruct students broadly, some narrowly. Some admit anyone, others exclude almost everyone who applies (while claiming to be inclusive, it should be noted). Some are essentially minor league athletic teams or hedge funds with ancillary academic departments bolted on. Some are outright scams.

In short, the terminology is a complete mess and if we were coming up with new labels from scratch today we would probably pick different ones. But this very confusion has led to an influx of students told to go to college who have no desire to be there, professors who want to research but have no desire to teach students actively resisting becoming educated, and employers who ostensibly can’t find workers with the “skills” they want (more on this later).

In explaining the liberal arts people sometime spout hippie bullshit about them being liberal because they “free your mind.” In fact their etymology comes from the Latin distinction between the artes liberales, or arts pursued for their own sake by free people, and artes serviles or artes mechanicae, the servile or mechanical arts, practical and vocational training intended for those who were either literally enslaved or needed to earn a living through work. It may be hard to imagine in a society as anti-intellectual as America’s, but the Roman notion of leisure involved intellectual development and what we might loosely call self-improvement. Their word for this leisurely study (otium) was the antonym of their word for business (negotium).

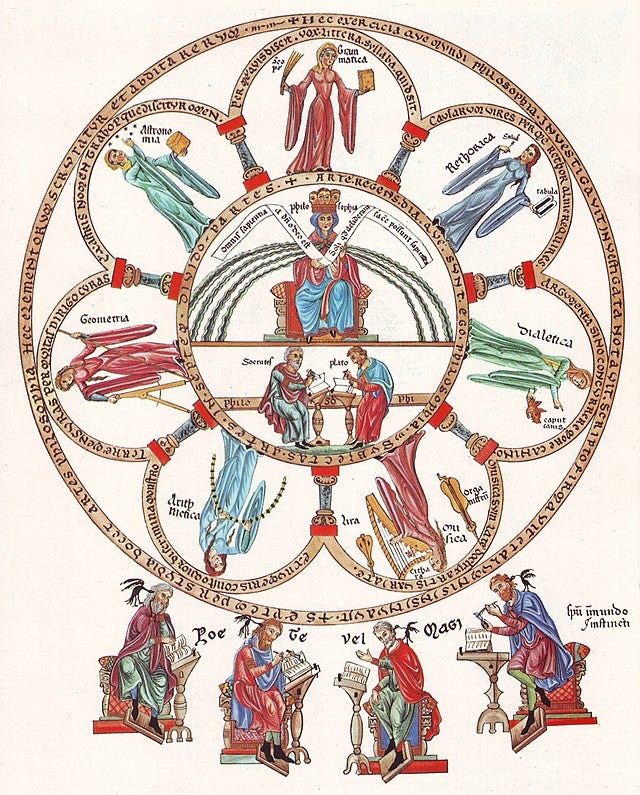

The exact enumeration and division of the liberal arts had some variations between their origins in Greece and transmission to Rome, but by the time of the medieval universities they were firmly divided into two groups, the trivium and the quadrivium, and it is striking how quantitative and analytical they were in comparison to today’s notions of the liberal arts.

The trivium (Latin meaning the crossroad of three paths) consisted of grammar, logic, and rhetoric and most closely (although imperfectly) aligns with the humanities. It was the lower division of the liberal arts, the foundation for the higher, more mathematical study in the quadrivium. Our English word trivial in fact derives from the status of the trivium the medieval hierarchy of learning. Grammar (specifically Latin grammar) was the most fundamental building block, and involved understanding the basic structure of language to describe the universe. Logic, the next rung up, consisted of the basic art of thinking in order to distinguish between truth and falsehood. Rhetoric involved combing these two lower rungs into the art of communication and persuasion.

The quadrivium (Latin meaning crossroad of four paths) consisted of arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy. Music, it should be noted, was not music performance or appreciation but essentially another form of mathematics involving harmonic frequencies. Thus arithmetic studied abstract numbers, geometry studied spatial numbers, music studied temporal numbers, and astronomy studied numbers in motion in the structure of the universe. (It should go without saying that the European medieval understanding of astronomy was completely wrong and their level of mathematics lagged what was then known in Arab, Indian, and Chinese civilization.)

I mentioned I will be treating the crisis in the humanities, specifically how in their current form they have undermined and endangered themselves and all of academia, in a separate post. However, since we have already discussed the confusion of terminology related to the classics, the liberal arts, and education I will briefly touch on that element of the story since it is too is a complete mess. Humanities derives from the Renaissance Latin studia humanitatis, a revival starting in the 14th century of classical rhetoric, grammar, poetry, history, and philosophy. The Italian word umanisti, i.e. humanists, referred to people engaged in the studia humanitatis by finding (physically) lost manuscripts of ancient Greek and Roman authors and editing them in order to revive the culture and literature of antiquity. Unfortunately this word humanism has been confusingly conflated with later developments to imply atheism or secularism, but this has nothing to do with Renaissance humanism. The vast majority of Renaissance humanists were Christian, although some (like Marsilio Ficino and Pico della Mirandola) dabbled in Kabbalah and Jewish mysticism.

I also mentioned I will be treating the blame for this conflation of education, liberal arts, and job training in a later post, but here is a brief preview in order from most to least culpable:

1) Employers claim they want college-educated workers for their skills, but as I have argued elsewhere this is unlikely because a) employers have no idea what they want, b) their job requirements are nonsense, and c) the people they do hire spend most of their time looking busy but doing nothing of economic value. Employers want workers with a base level of intelligence, but most of all with a high degree of conscientiousness and rule-following, very little critical thought, and the basic social mores to navigate office life. They mostly want people who do what they’re told without asking too many question and they use the process of college admission and attendance as a proxy to screen for these traits, but they have virtually no interest in what students have or have not learned there.

2) College administrators, seeing the widening wage gap between those with and without college degrees, engaged in massive rent-seeking behavior, jacking up tuition costs beyond belief. Very little of this money went to actual education; most went to country club amenities for their campuses and (surprise, surprise) more and more college administrators, a grossly inflating panoply of deans, provosts, and chancellors. With students essentially forced to buy their way into the middle class by going to college, regardless of whether they had any interest to or not, and the government subsidizing the loans necessary to pay, it was only a matter of time before shit hit the fan (which it very much has now).

3) Faculty members meanwhile decided they would rather be activists than scholars. They decided to teach their students what, instead of how, to think as progressive identity politics came to completely dominate the academy. Much like the French Revolution this movement started with some legitimate grievances and then devolved into madness, for it required belief in things that are so bizarre they make Aristotle’s views on eels and women’s teeth look normal in comparison. But although this illiberal, humorless, scolding, neo-Puritanical movement was merely annoying before October 7, it become truly noxious afterwards. Trump’s attacks on Harvard and other universities are disgraceful and dangerous but hardly surprising given that the movement often seemed to go out of its way to provoke and antagonize the non-elite taxpayers on whose largess it depended.

The liberal arts properly understood are neither job training nor are they the forcing of textual interpretation into predetermined ideologies. Combined with the scientific method (which they historically gave rise to) they give an excellent way to understand the universe, and if they are to survive they would do well to get back to the spirit of their origins.