“Firms have jobs, but can’t find appropriate workers. The workers want to work, but can’t find appropriate jobs.”

“[P]eople don’t have the job skills for the jobs that are open.”

These quotes sound like very recent discourse about AI, but they are actually from 2010, the first from Minneapolis Federal Reserve president Narayana Kocherlakota, the second from Bill Clinton. Paul Krugman rightly denounced these views as “humbug” at the time, but they represented a very serious view among pundits and economists that the high unemployment following the financial panic and Great Recession of 2007 to 2009 was not cyclical, caused by low demand, but rather structural, caused by a fundamental mismatch between employees’ skills and employers’ needs.1

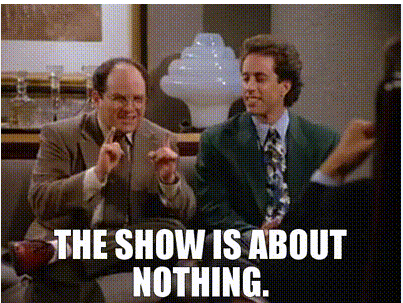

Today the handwringing is about AI in the job market, and I will argue that this too is humbug, but not for the reasons usually proffered. Economists and pundits talk about skills and jobs as if they had never set foot in a modern office environment because, if they had, they would realize that most workers spend the vast majority of each day looking busy but doing nothing whatsoever.

Let me preface my remarks by saying that I am speaking based only on my (in the jargon of the decolonize crazies) “lived experience” about white-collar, upper middle class, professional/managerial work. Blue-collar workers who make things with their hands no doubt have a very different “lived experience” about work, but the AI discourse is not about them right now and probably won’t be until robotics technology becomes as superficially impressive seeming as large language model chatbots.

Consider now a recent New York Times op-ed “I’m a LinkedIn Executive. I See the Bottom Rung of the Career Ladder Breaking”2 by Aneesh Raman, Chief Economic Opportunity Officer at LinkedIn, who argues that AI is endangering the pipeline of entry-level workers and that we must ensure that “workers are learning the skills employers are starting to demand.”

I will address the substance of Raman’s argument shortly, but there are two clues that he might be full of bullshit. First, his title is Chief Economic Opportunity Officer – this is a ridiculous, made-up job that is not real. The US Department of Labor in fact maintains a minutely detailed 285 page Standard Occupational Classification Manual3 and Chief Economic Opportunity Officer is nowhere in it; it is very clear from his job title alone that Raman spends the vast majority of each day doing virtually nothing. Second, Raman works at LinkedIn, a company that depends entirely for its existence on people either posting content or scrolling and reading content, but most significantly NOT DOING THEIR JOBS. Indeed, what started as website for posting jobs and recruiting talent is now largely a social network for professionals to have full blown mental breakdowns in public and for other professionals to gawk at them in disbelief.

Raman argues that workers need to learn skills that employers want. This would be great … if employers had any idea what they wanted. Job listings in tech used to seek “rock stars” and “ninjas” until this was deemed problematic and offensive to actual ninjas. I just did a random search for jobs on LinkedIn and found a company that wants someone to “work with the global teams to enhance procedures and best practices ensuring processes are globally aligned.” Another seeks workers to “continually review and improve processes to achieve maximum efficiency and effectiveness.” A third needs a worker who “establishes, encourages and builds strong business relationships with appropriate groups.”

These requirements are complete nonsense; they are pablum, a meandering word salad that a child trying to parrot business-speak would come up with. And the people who end up getting these jobs will spend most of their time doing nothing because that is exactly what the help wanted ads ask for.

Think of the actual tasks that happen on a daily basis in a modern office environment. Interns make copies and fetch coffee. Low level employees do the digital equivalent of shuffling paper from one side of the desk to another in software like Trello or Jira. Middle managers fill up the day with pointless meetings. Senior managers create new committees, subcommittees, and working groups. C-level executives play golf. People say things like “Let’s put a pin in this and circle back” or “Let’s reach out to HR.” Employees scroll through LinkedIn looking for new jobs while hiring managers in the next room scroll through LinkedIn looking for new recruits at other companies who are job hunting and not doing their current jobs. But most importantly they are all devoting a tiny fraction of their time and energy anything economically useful.

Techno-utopians like to argue that AI will improve productivity, but this is clearly the last thing that companies want. Imagine if you could do an entire day’s work by 11 am and then leave and go home. You would by definition (output per hour) be highly productive. But you would also be fired for leaving at 11 am. Companies would much rather have people looking busy for a full day than actually being productive. Consider the recent case of Robert W. Baird, a boutique Midwestern investment bank, where junior analysts working 110 hour weeks were (allegedly) called together for a team pizza party only to be chastised for not working enough.4 I am not a trained economist, but I’m going to guess that the law of diminishing returns says that the marginal output from your 111th weekly hour of work compared to your 110th weekly hour of work is pretty low. But the executives at Baird, or the those at Goldman and all the other comparable banks, are very obviously not interested in economic output at all; they are engaged in hazing, in building esprit de corp like a military boot camp. The workers are very busy doing nothing of any economic value.

In the end, it does not matter very much whether the modern office place is ready for AI. Companies were probably not ready for the Internet in 1995 when US GDP was $7.6 trillion. By the time of the 2010 structural/cyclical unemployment debate it had risen to $15 trillion. Today in 2025, as the histrionics about AI grow, it is just under $30 trillion. Capitalism has lead to a rise in material living standards such that the poorest Americans alive today enjoy luxuries beyond the imagination of almost everyone who lived before the Industrial Revolution. And yet somehow we are to believe that the system is too weak and fragile to handle entry-level workers being disrupted by a new technology? Spoiler alert, here’s what’s going to happen: one of those entry-level workers is going to figure out AI and then found a new company, and then we’ll all have jobs doing nothing there just like we have jobs doing nothing now.

Thinking about the insanity of our discourse about AI, jobs, and skills reminds me of something I used to notice back when I was job hunting in the late 1990s after I graduated from college: every single helped wanted ad seemed to include the phrase “fast-paced office environment.” I actually believed this until I had a few jobs under my belt and realized that if every single office is “fast-paced,” that just means they all have the same normal pace. And that pace involves doing a whole lot of nothing.

This is a great post - packed with enough useful information, wit, and wisdom to satisfy even the busiest C-suite executive - well done!!