And we’re back! I trust you all enjoyed the Doggy days of August, but we are resuming regular publication of essays now. I have a few more subscribers than when I published my last essay on July 31, I Meet the NY Times Women Struggling with Dating, thanks to the New York Times publishing a couple of articles in in a row by the only two people on the planet worse at dating than me. This gave me what comedy writers refer to as a layup and, by proxy, thousands of more views than my writing typically gets.

A glance at my newsletter archive will confirm that I usually do not write about dating or any evergreen topic likely to be popular with normal readers (although to be fair the war of the sexes is one of the oldest tropes in literature). I therefore thought I would preface this week’s installment with a brief note about the newsletter itself. Anyone who is desperate to learn about Athanasius Kircher is welcome to skip this part and go straight to the good stuff below.

I said in my inaugural Welcome to my Substack post that I would do anything, including starting a newsletter, to procrastinate from writing my book. That part was not a bit; I am planning to write a book starting in 2026. I am reluctant to share the details yet, but it will be a popular history book related to early modern Italy in the vein of the great Ross King (author of, among many others, Brunelleschi's Dome and Michelangelo and the Pope's Ceiling). My goal in starting this newsletter was twofold: 1) to start writing again, to get the rust out and 2) to practice promoting my hypothetical book by promoting this actual Substack. I think both have been going well.

My very loose plan for this Substack now is each month to do 1) a history piece (like today’s) that will often but not always be related to my book 2) a piece in the Behold the Treasures of my Library series where I examine a book that is in no way rare but which was somehow meaningful to me 3) a politics piece 4) a piece that is either pure humor or about something popular with normal people (health, finance, fitness, etc.). It is also very likely that Doggy cartoons will be back in December.

Athanasius Kircher

With those preliminaries out of the way, let us turn to Athanasius Kircher (1602 – 1680), one of the most eccentric and curious figures of early modern Europe, a scholar and Jesuit priest born in Germany who spent most of his career in Rome. He was a true polymath, with interests ranging from medicine to astronomy to geology to Egyptology. He was often wrong, and wrong in the most spectacular fashion.

His birthplace was the town Geisa, near Fulda, and he entered the novitiate of the Society of Jesus, as the Jesuits are formally known, around 1618. He received early instruction in Hebrew and Syriac (he would ultimately claim to know well over twelve languages) and excelled in mathematics and volcanology. Ordained as a priest in 1628, he taught at the University of Würzburg where he apparently had a prophetic vision of the city’s attack and capture by Protestants. A few years later, in 1633, he was supposed to go to Vienna to replace Kepler as the Habsburg emperor’s mathematician, but following a shipwreck and some papal intervention he ended up in Rome where he spent the rest of his career.

Officially the chair of mathematics at the Collegio Romano, Kircher in some sense became a one man think tank. There was a reason for this playing out behind the scenes: at almost exactly the same time that Kircher arrived in the Eternal City, the Barberini pope Urban VIII had overseen the condemnation of Galileo Galilei by the Roman Inquisition. Although his sentence was commuted to house arrest, and although most high ranking Jesuits believed that Copernicus was right and that Aristotle was wrong about the heliocentric structure of the solar system, the Tuscan astronomer had gone too far in his open contempt for established authority. The powerful cardinale nipote Francesco Barberini, Kircher’s mentor, likely thought that the German scholar’s “flamboyant showmanship” as an intellectual could prove to be a valuable—yet orthodox—counterpoint to the Galileo fiasco.1

Kircher’s 40-odd books, most lavishly illustrated and published under his own name (unlike most Jesuits who used pseudonyms), became the international face of his intellectual fame. In Rome itself the German was equally famous for his Museo kircheriano, or Musaeum as he called it in Latin. This was essentially what the Germans call a Kunst- und Wunderkammer, a cabinet of curiosities, although Kircher’s was heavier on the Wunder side. The nucleus was formed by the aristocrat Alfonso Donnini, and Kircher took it over and grew it into sprawling museum of antiquities, scientific instruments, bizarre inventions, and random bric-à-brac. The collection remained intact, incidentally, long after his death and was only dispersed to other institutions in 1916.

Kircher’s first book in Rome (he had published previously in Germany) was the 1636 Prodromus Coptus, the Coptic or Egyptian Forerunner, dedicated to Francesco Barberini. This would be the first of many tomes on Egypt in which Kircher would claim to understand hieroglyphics (he didn’t), although he was correct in assessing the link between ancient Egyptian language and Coptic. Of course people in Rome had been fascinated with Egypt ever since antiquity. In the early modern period this fascination was revived as many obelisks were erected in various piazze still to be seen today.

Kircher’s basic error was assuming that hieroglyphics were all ideograms, pictorial symbols representing ideas, but although some of them were the vast majority were in fact phonograms, phonetic signs representing sounds of the spoken language. The role of Egypt and Egyptian language was extremely important in the Renaissance and Baroque periods, especially in the so-called prisca theologia, the ancient theology, which attempted to demonstrate that various pagan thinkers had foreseen Christianity and that their philosophy contained Christian truths hidden as esoteric allegories. Hermes Trismegistus, the thrice great Hermes, a syncretic amalgamation of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth, the putative author of the Corpus Hermeticum, played a key role here, as did Horapollo, the supposed ancient Greek author of the treatise Hieroglyphica, and more modern figures like the Italian humanist Pietro Valeriano who penned the Hieroglyphica sive de sacris Aegyptiorum litteris commentarii. Jesuits had an additional reason for wanting to crack the code of hieroglyphics, for they thought a universal language based on pictures could help them in their missionary work spreading the Gospel.2

Kircher’s only spell away from Rome after arriving came in 1637 when he accompanied a young German prince who had converted to Catholicism and would ultimately be made a cardinal on an educational tour of southern Italy, Sicily, and Malta. This gave Kircher an opportunity to expand his scientific studies, exploring both Vesuvius and Mount Etna as well as the Strait of Messina and engaging in astronomical study on Malta. He would also meet and befriend, on Malta, Fabio Chigi who would later become Pope Alexander VII.

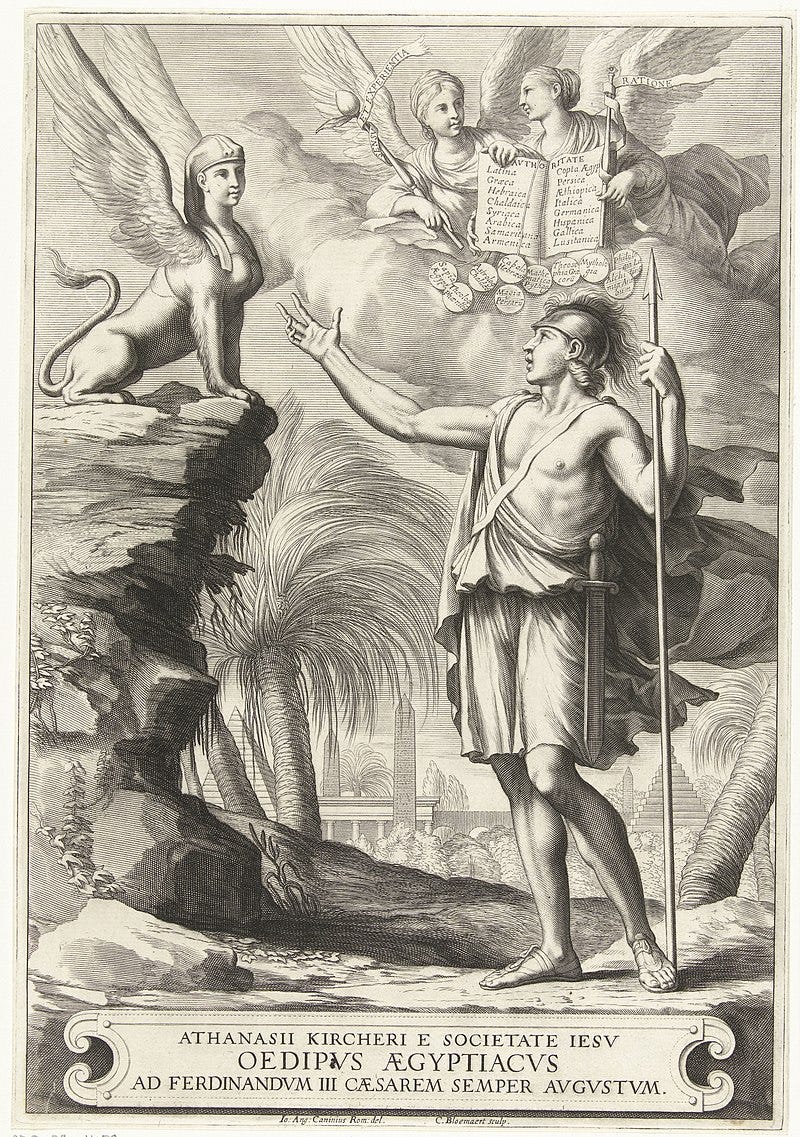

Back in Rome, Kircher would publish his second treatise on Egypt, Lingua Aegyptiaca Restituta, in 1643, his last under the Barberini pontificate. This was based on Arabic-Coptic manuscripts given to Kircher by Pietro della Valle who had travelled widely in Egypt, the Levant, and points further East. Kircher’s largest work on Egypt was the Oedipus Aegyptiacus, published in four massive folios between 1652 and 1654, which consisted largely of spurious translations of hieroglyphics based on the so-called Bembini Tablet (also known as the Mensa Isiaca), a late antique Roman bronze tablet in the Egyptian style, as well as massive digressions on Chaldean astrology, the Kabbalah, and Pythagorean and Neoplatonic philosophy.

Kircher also published, in the Jubilee year of 1650, his Obeliscus Pamphilius which commemorated the erection of the obelisk in the Piazza Navona, in front of the family palazzo of Urban VIII’s successor the Pamphilj Pope Innocent X, as the centerpiece of Bernini’s famous Fountain of the Four Rivers. The obelisk had been commissioned by the emperor Domitian and was later moved to the Via Appia by Maxentius where it fell into ruin. Kircher’s erroneous Latin translation of the engraved hieroglyphics on it are on panels around the obelisk’s pedestal, and the entire iconographic program of the fountain, a common subterranean source feeding the Nile, the Ganges, the Rio de la Plata, and the Danube reflects the German scholar’s muddled understanding of geography.

Egypt was of course far from Kircher’s only interest. In his youth he had wanted to be a missionary in China, like Matteo Ricci, and 1667 saw the publication of his massive encyclopedic China Illustrata. Immensely popular and soon translated from Latin into multiple vernacular languages, the material in China Illustrata ranged from mostly accurate information about cartography and the Nestorian Christians of China to extremely fanciful fare about dragons and the relationship between Chinese script and Egyptian hieroglyphs. Around this time Kircher also came into possession of the Voynich Manuscript, now at Yale, which Jan Marek Marci had sent him to decipher.

In the 1670s Kircher published two books demonstrating how modern science supported the biblical narrative of the book of Genesis. The first was the 1675 Arca Noë (Noah’s Arc) and the second the 1679 Turris Babel (The Tower of Babel). Kircher did detailed mathematical analysis of the dimensions of the arc and the tower and the logistics involved in each story, although as usual his writing sprawled out of control with digressions into comparative religion, the origins of language, and the wonders of the ancient world.

I have focused on Kircher’s studies of Egypt and language because that is most interesting to me, but it really only scratches the surface of the German’s intellectual breadth. I have alluded to his interest in volcanos and earthquakes, but he was also fascinated by and wrote lengthy treatises on magnets, fossils, tides, Atlantis, spontaneous generation, and the origin of plagues. He developed a prototype of the magic lantern for projecting images, constructed a magnetic clock, invented new musical instruments, and did work anticipating abstract symbolic logic based on combinatorics. All in all he was, as the title of a scholarly anthology about him says, the last man who knew everything.3

And yet even in his own time, and especially towards the end of his life, there were signs that Kircher was something of a ridiculous figure too. Descartes called him more a charlatan than a savant and Leibniz panned his China Illustrata. Before publication all books at this time were subject to examination by censors to screen for heresy, and one of Kircher’s censors, the Jesuit Melchior Inchofer, wrote a thinly veiled satire The Monarchy of the Solipsists featuring an Egyptian vagabond babbling about the moon while seated on a wooden crocodile.4 Censors of his later books expressed concern about possible sympathy Kircher may have had for Giordano Bruno, the heretical philosopher burned at the stake in the Campo de’ Fiori in 1600.

In the centuries after Kircher’s death, knowledge would become increasingly specialized. Archaeology, linguistics, and “natural philosophy” became scientific as the Enlightenment progressed, and it would never again be possible for anyone to know—or claim to know—everything that Kircher had devoted his life to. By the time Champollion and Young actually deciphered hieroglyphics with the Rosetta Stone in the nineteenth century Kircher had been largely forgotten.

See Ingrid Rowland, The Ecstatic Journey: Athanasius Kircher in Baroque Rome, Chicago 2000 pp. 1-3.

Rowland, p. 8.

Paula Findlen ed., Athanasius Kircher: The Last Man Who Knew Everything, Routledge 2004.

Rowland, p. 19.